Deployment Strategies Defined

Let’s talk about deployments. This topic used to be considered an uninteresting implementation detail, but is now becoming a fundamental element for modern systems. I feel like everyone understand its importance, and is working to build solutions around it, but we are missing some structure and definition. People use different terms for same meanings, or same terms for different meanings. This leads to other people reinventing the wheel trying to solve their problems. We need a common understanding of this topic in order to build better tools, make better decisions, and simplify communication with each other.

This post is my attempt to list and define those common deployment strategies, which I called:

- Reckless Deployment

- Rolling Upgrade

- Blue/Green Deployment

- Canary Deployment

- Versioned Deployment

There are probably other names and terms you expected to see on this list. I’d argue that those “missing” terms can be seen as variants of these primary strategies.

And one final note before we begin: this post is about definitions, methodologies and approaches and not about how to implement them in any technology stack. A technical tutorial will follow in another post. Stay tuned!

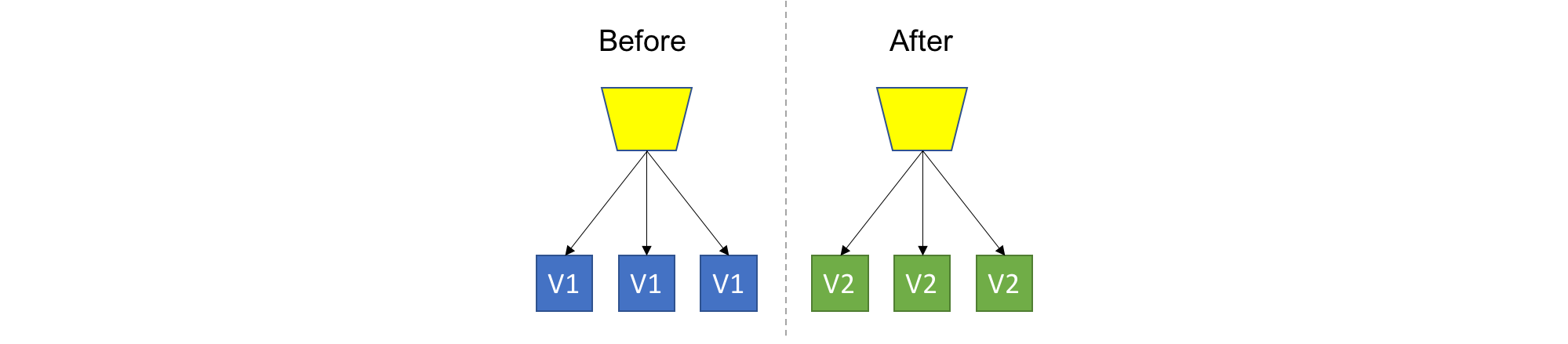

Reckless Deployment

a.k.a: Highlander, Simple

TL;DR: Destroy the old, provision the new, don’t care for consequences.

This is the easiest strategy, which means we just nuke everything, and recreate the new version. Usually good for Dev/Test scenarios or very low impact applications. Not much to add here…

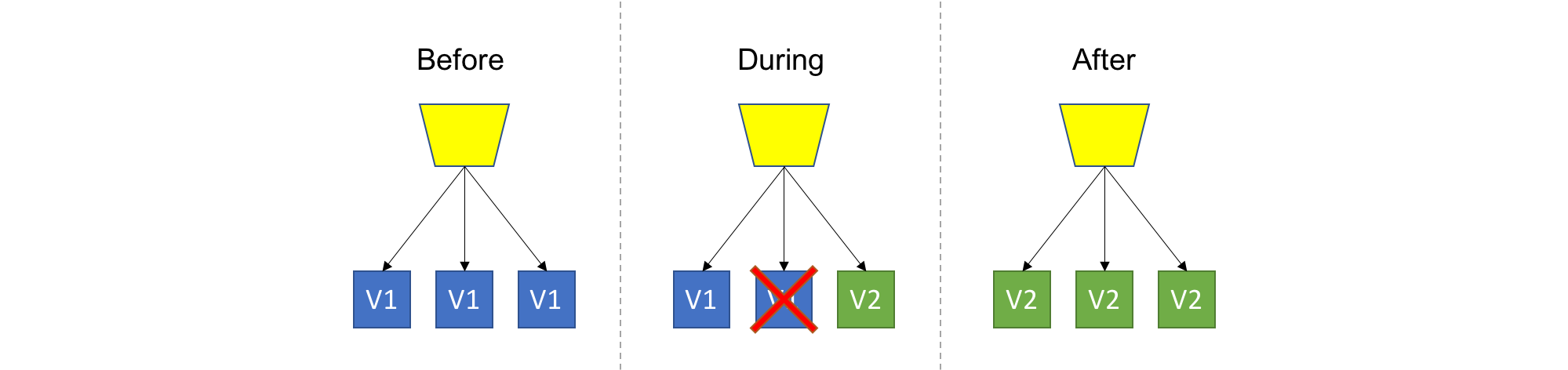

Rolling Upgrade

a.k.a: Gradual Deployment

TL;DR: Introduce new version of the code into the existing deployment, gradually ramping up while decommissioning old code.

This is a basic strategy that is about adding new code into an existing deployment. The existing deployment becomes a heterogeneous pool of old version and new version, with the end goal of slowly replacing all old instances with the new instances. The terms ‘Instance’ and ‘Pool’ can mean different things depending on your technology stack (VM, Container, Process, etc…).

Health and monitoring

An important aspect of this strategy is health checking and monitoring. The whole point of gradually introducing new code is to be able to control damages in case of an unexpected issues with the new code, and in order to do that we have to know how the the new version is doing. Therefore, health checking and monitoring is essential.

Roll back

If we determine that the deployment is not going well, we could stop the rollout, and even cancel and undo the deployment (a.k.a roll back).

Backward compatibility

Since new code and old code live side-by-side under the same roof, users might be routed to either one of the versions arbitrarily, so backward compatibility should be a major concern for you if you are using this strategy.

Closely related

You might be thinking about doing some smart routing of users to allow some users to consistently get a specific version, or to expose only a subset of users to new version - You are on the right track, but then I wouldn’t call it a Rolling Upgrade anymore. Keep reading to see where I’m going at.

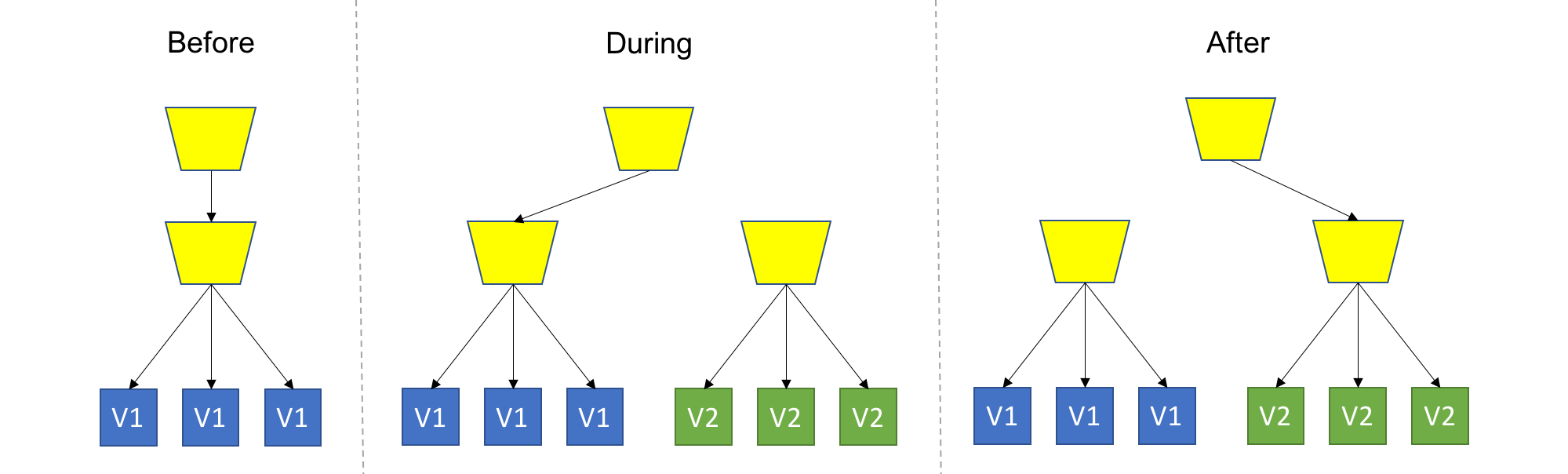

Blue/Green Deployment

a.k.a: Red/Black, Staged deployment, Swapping Slots

TL;DR: Spin up a new separate deployment for the new version, without affecting the current one. Test the new version, and once ready start routing users to the new version.

This is the safest strategy, and is used by many for production workloads. To provide that safety, we won’t touch anything that’s currently running, and provision an entire copy of the application, or the module we are upgrading aside. It’s up to you to decide on the scope of deployment (or scope of isolation), for example: Do you recreate the entire system, or just the updated module? Do you create a separate Load Balancer for the new version deployment, or add a new rule to the existing Load Balancer? Do you share configuration between version? These are just some of the questions that might come up, and it’s up to you or your tools to decide.

One thing is for sure - the new version should be completely isolated from the current version deployment, this is in contrast to Rolling Upgrade where, for the duration of the upgrade, we had a heterogeneous deployments consisting of old and new code. As a consequence, backward compatibility is not mandatory here.

Once the new version is live, you should test it however and how long you need to. Since the current version is still live and serving, there’s no rush to finalize the deployment. At this point users are still unaware of the update.

When you get confident enough with the quality of the version, you would start routing users to the new version instead of the old version. It can be all users at once (a.k.a cut-off or cut-over), or gradually add more users to the new version.

Draining

A common practice is “draining” the old deployment before transitioning, meaning allowing current active sessions to end naturally, and only start new sessions using the new version.

Switch Back

Usually you will want to keep the old one around even after the full transition had completed, just to be sure you can undo and switch back to the old working version easily.

Stage

A common variant of this strategy is staged deployment/slot swapping. The scope of the deployment (or scope of isolation) in this case is the entire application (meaning we have an entire copy of the whole system on stand-by). In this practice we always have 2 copied of our application infrastructure around, even if an upgrade is not currently in progress. One environment is the production, and the other is pre-production, usually called ‘stage’. We can use the stage regularly for stuff like QA/UAT/Repros/CI. We always deploy to stage, never to production. Therefore, the stage will always be ahead of prod, representing the latest candidate for production. As in regular Blue/Green, we should test and validate stage without affecting prod, and once we are good for deployment, we simply swap the routing between the two environments, meaning stage becomes prod and prod becomes stage. This is usually done using updating DNS records (but not necessarily). Again, we can easily swap back if something bad happens.

Closely related

You might be thinking about exposing that Stage environment (or that new “green” deployment) for actual users to try. This is a good idea, which I call Canary Deployment, It’s described next.

Canary Deployment

a.k.a: Ringed Deployment, Feature toggling, Dark features, Silent launch, A/B testing, Testing in production.

TL;DR: Deploy the new version into production alongside the old one, carefully controlling who gets to use the new version. Monitor and tune the experiment while gradually expanding it’s population.

This is the holy grail of deployment practices. Also the hardest to achieve.

It can be seen as an advanced usage of one of the previous strategies: Use any strategy that you’d like to introduce new code into the system, with the key difference of allowing real users to use the new version in production. Naturally, you wouldn’t want all users to get all new, premature features, so you’ll want to control which users get which pieces of the new version. This can be implemented at the load balancing/proxy layer, using application settings, at runtime, or any other way that works for you.

The basic and common implementation of Canary uses Blue/Green Deployment with the addition of smart routing of some users to the new, “green” version.

More advanced implementation will go beyond the enhanced Blue/Green technique, and deploy at a more granular level. Canary is all about control and supervision, the more granular you can control your components, the more advanced your canary deployment is.

More monitoring

We already mentioned this before, but I’ll restate it again with even greater significance this time. None of these advanced patterns will work without excellent monitoring in place. For Canary, consider going beyond the basic vitals checks, perhaps look at performance or user experience metrics. With good observability, Canary will let you move from thinking about deploying a functioning version, to deploy the best version.

A/B Testing

An advanced variant is shipping multiple different versions into production, and running experiments on real users and their reaction to each version. Now we digress from the topic of deployment strategies to more about mature product planning approaches, but I mention this here because the deployment strategy is the crucial foundation of any of these advanced business related strategies and therefore are often closely related.

Dark features

An extreme version of Canary Deployment/Testing in Production is shipping turned off features to production, and turning them on selectively for some users (think beta/preview testers). To work like this your system needs to be designed in a very modular way, such that the unit of deployment is a feature, and the application is dynamically composed of features that can be individually toggled. A dedicated release management system for managing which features are active for which users is not a bad idea in this case.

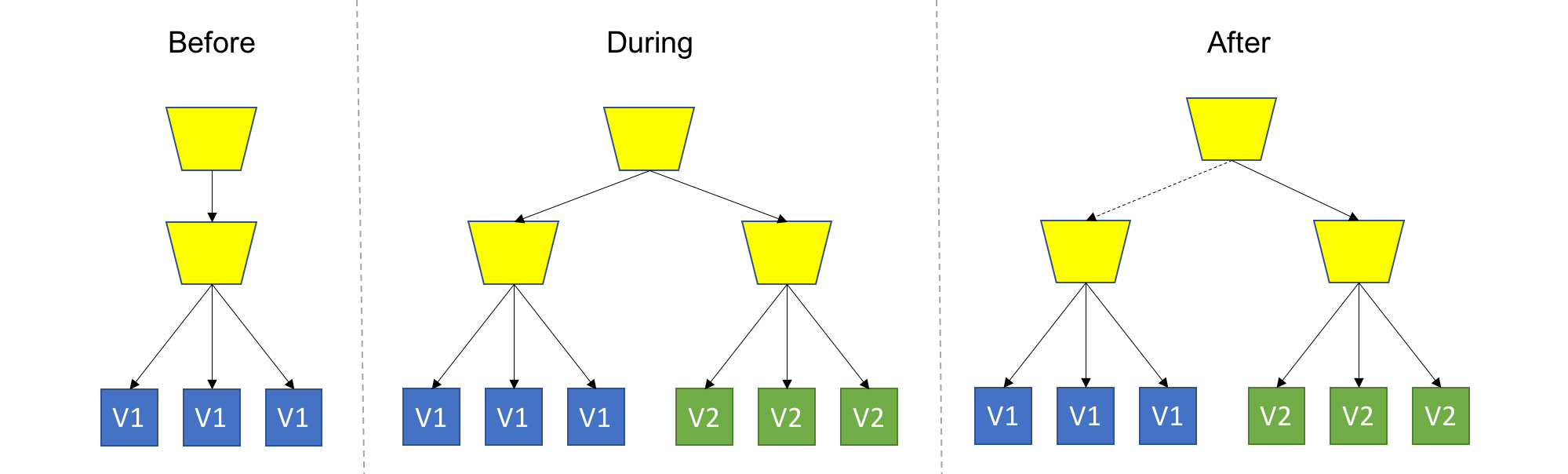

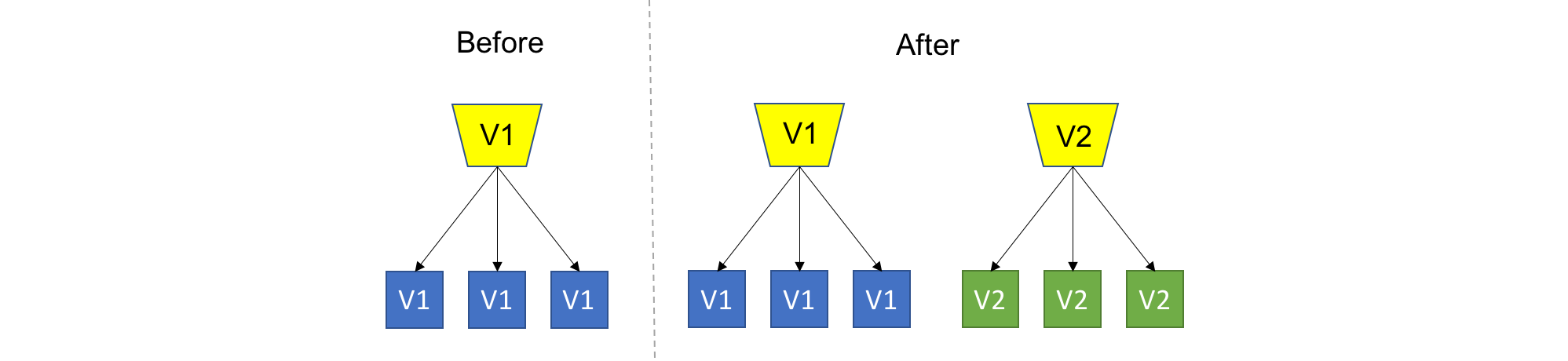

Versioned Deployment

TL;DR: Always keep all versions alive, while letting the user choose which version to use

I wasn’t sure if I this one belonged here, since it’s borderline an architecture pattern or API design pattern, rather then a strict deployment method. Still, I think it has the potential to affect your deployment approach so I do list it as a deployment strategy here.

What if you didn’t have to choose between versions, and you could always keep all versions running in production? This appealing strategy is especially popular amongst API developers. In this example, all API versions will always be available (never remove a working version) and the user will choose which version they want to work with. This is in contrast to every other strategy where we (not the user) decided which version users will use.

The obvious complications are the extra capacity to host legacy versions, and maintaining shared data sources across versions. But if you care enough about backward compatibility, and can spare the extra capacity, the benefits will outweigh these complications.

As for the deployment of this strategy, it’s very straightforward: just deploy the new version. Since everything is always explicitly versioned, it’s easy to just trow out a new versioned deployment, there are no consequences. The beauty is that users have to explicitly ask to use the new version (or any version), so your deployment platform doesn’t have to care about transitioning users between versions.

API Design

I won’t go into specific examples here because this post is not about designing APIs. But I will suggest that if you are interested in this strategy, take a look how Microsoft designed their Azure Resource Manager (ARM) API. It is a wonderful example of this pattern, and for the design of REST APIs in general.

Summary

That’s it! Those were the deployment strategies that I consider essential, and how I think their are defined and differ.

We covered the following strategies:

- Reckless Deployment - If you don’t care.

- Rolling Upgrade - Deploy gradually in order to allow time to roll back.

- Blue/Green Deployment - Encourages safety by protecting the production service from any altering operation, directing these operations to a side environment.

- Canary - Which exposes new versions to real users.

- Versioned Deployment - Which is a special purpose design that allows multiple versions to coexist forever.

@itaysk

@itaysk

itaysk

itaysk

itaysk

itaysk